Holes in the Problem-Solving Schema

We are trained to “solve” problems while ignoring the root causes.

I wrote last week that institutions and norms aren’t inherently good. A central part of that argument was that many of the institutions Trump is attacking are not just lacking inherent goodness - they are actually somewhat bad. My local public school system is bad in many obvious ways, and my local public transit system has poor geographic coverage, is routinely late, and doesn’t run on Sundays.

A couple days ago Angie Schmitt published a piece with a similar argument. Schmitt intuits that people passionately defending public institutions do not use those systems, because real users are consistently and reasonably frustrated. She wrote,

“Here’s my suspicion about all these people who are always memeing about how ideal and magical libraries are: I think they don’t use them. When I go to the library, a lot of times it’s sorta deserted. Everyone’s at home on their computer talking about how they love libraries, presumably. Trust me when I say, the stacks on the fourth floor — business section — of the Cleveland Library main branch — never crowded.”

Schmitt is a national expert in sustainable transportation and a frequent user of her public library. Her criticism comes from a place of love and familiarity. She doesn’t want those systems destroyed or defended - she wants them improved.

My initial reaction to Schmitt’s piece was excitement. It was cool to see a real-life expert share my view. But then I got to thinking about why these systems are so hard to improve in the first place. If regular users of public transit, libraries, schools, or parks can easily point out what’s wrong, why can’t political leaders get to what works? While there’s certainly a lot of contributing factors, I think a big reason institutions are hard to improve is because of how leaders are trained to diagnose and solve problems.

My Personal Experience with Formal “Problem Solving”

I received formal training in problem solving while I was getting my master’s degree in international development/public policy. My program was funded by a former COO and director of Coca Cola. This will be relevant to the story later.

During my final semester I took a class that was jointly offered by the university’s MBA program. This class sent groups of MBA students (and a few policy students like myself) into under-resourced parts of the world to act as short term consultants for businesses and nonprofits. My team went to Brazil to work with an NGO trying to prevent deforestation in the Amazon rainforest. A key part of this NGO’s strategy was to increase profits for farmers and laborers in the rainforest as a natural deterrent for illegal logging. The idea was that if farmers could legally make good money, they wouldn’t need to turn to illegal activity to support themselves. My team of grad students was working specifically on increasing profits for rural guaraná farmers.

Guaraná seeds are a natural source of caffeine, and the primary buyer is beverage companies - specifically Coca Cola. The farmers would harvest the seeds by hand, dry them for several days in the sun, and then take them upriver by boat to sell to Coca Cola. Once Coca Cola got all the seeds they needed they would leave town, and any farmer who missed the sale window would lose nearly all of their income. Given that it was at least 15 hours by boat to the sale point and most of the farmers didn’t have a boat and needed to hitch rides, it was very common for these men to get almost nothing for their labor.

When a group of poor farmers keeps getting ripped off by the same multibillion dollar company, the most obvious solution, potentially the only viable solution, is to get that company to be a little more ethical. The cleanest option for my team was to get Coca Cola to guarantee a price floor so nobody would be destitute, or make it easier for farmers to access the sale point so random happenstance wouldn’t deprive someone of a season’s worth of income. But when my team met with Coca Cola representatives we were told this was not an option. Coke would not change their dealings with the farmers. If the NGO we were representing wanted to stay in Coke’s good graces, we had to find another solution.

My team whipped up a recommendation about turning the guaraná seeds into a powder that could be stored and sold later. While this would give the farmers a chance to earn some revenue, it would be much less than selling directly to Coke. We shared the powdered guaraná recommendation with the NGO and our professors. The NGO and our professors were very pleased with our recommendation.

We never discussed it with the farmers.

Problem-Solving without a Cause

I estimate that my University spent around $15,000 sending a group of amateur consultants deep into the rainforest for 2 weeks to “solve” this problem. A significant chunk of that money, and the entire program from which I was educated, came from the former COO of Coca Cola.

But because we were not allowed to engage Coca Cola in any solutions, we basically were not allowed to solve the problem at all. After learning that Coke would not negotiate with the farmers, a creative problem solver might have said, hey, let’s go back to the university and use their contacts with Coca Cola to push this solution from a different angle. After all, there’s entire buildings named after their former director. Yet even though my university clearly had ways to get in touch with senior leadership at Coca Cola, this was never an option. There was never a path to get Coca Cola to treat their supply chain laborers like dignified human beings.

At face value this looks like a straightforward anti-capitalist argument. Coke is callously managing their supply chains, unwilling to make small changes that would have a dramatic impact on the quality of life for countless farmers and families. The NGO and the university don’t even consider asking Coke to change their ways, because they are afraid of upsetting one of their main funders. So even though Coke is creating the problem, by donating juuuust enough money they can make it look like they’re part of the solution - while taking the heat of their own involvement entirely. Of course, Coke will give money to a private university in the United States, and to a large NGO in Brazil, but they won’t give a few more pennies to the farmers who actually need it. With Coke’s corporate behavior change off the table, and Coke’s financial contributions off the table, us “problem solvers” were left to nibble at the edges of a solution while ignoring the core issue.

Two business school professors at NYU wrote into the Times earlier this month making this same argument in their essay “The Impossible Math of Philanthropy.” They said,

Americans typically understand charities as organizations that pick up where the government leaves off — championing the poor, the environment, the sick and the marginalized. But this framing is incomplete, and frankly misleading. More often than not, charities work to mitigate harms caused by business. Every year, corporations externalize trillions in costs to society and the planet. Nonprofits form to absorb those costs but have at their disposal only a tiny portion of the profits that corporations were able to generate by externalizing those costs in the first place. This is what makes charity such a good deal for businesses and their owners: They can earn moral credit for donating a penny to a problem they made a dollar creating.

I agree with this argument, but my story about the guaraná farmers isn’t another anti-capitalist essay. It’s a critique of how institutions train people to solve problems. My university is one of dozens that train the business, philanthropy, and policy leaders of tomorrow. Although the universities are operating independently, they share their approach to problem solving and share the same blind spots that I saw on my short trip to Brazil. These universities have created a problem-solving schema that their graduates use to “fix” systems like public schools, public transportation, and public libraries.

This schema was drilled into me and thousands of other students in similar programs across the country, and thousands more in the years since I have graduated. And this problem-solving schema deliberately ignores key causes of the problem. The professional problem-solvers are taught to look away from the sins of corporations in the name of partnerships and philanthropy. We are taught that a good recommendation is one that can solve a sliver of the problem (i.e., powdered guaraná) without upsetting institutional interests. We are taught that it’s okay for the poor to stay poor, as long as the powers that be don’t have to change anything they are doing.

The Next Wave of Centrist Democrat Ideas: The Abundance Agenda

Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson have started writing extensively about the Abundance Agenda.

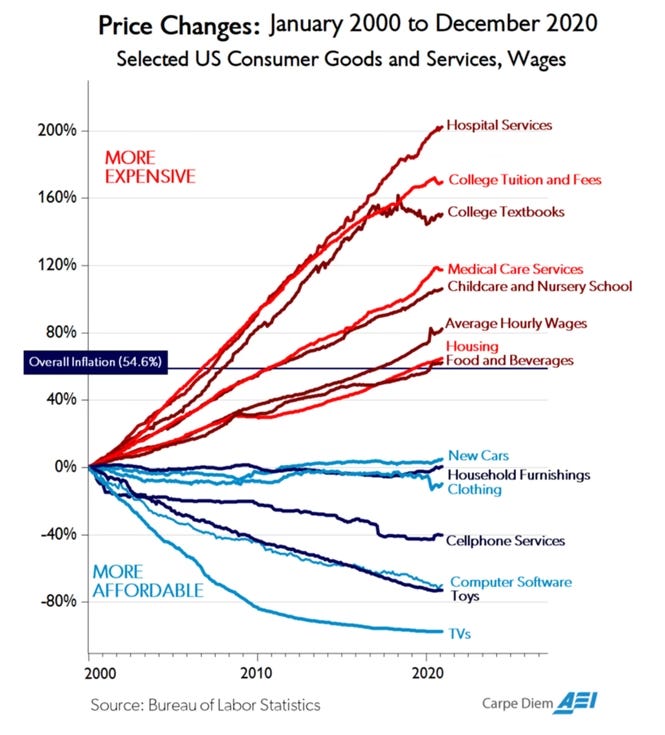

The abundance agenda starts with this chart, and argues that all the dramatic increases in pricing can be solved by removing the constraints on supply. These constraints change depending on the sector - zoning laws for housing, physician training requirements for hospital services, admission rates for college tuition - and Thompson and Klein apply this supply-side argument to basically every aspect of American life. Given their status among Democratic thinkers (Klein in particular) the abundance agenda is almost certainly going to be picked up by centrist Democrats in the coming months. Their book on the topic comes out next month, and I can almost guarantee that the abundance agenda will be part of the Democrat’s 2028 primary debates.

The abundance agenda reveals the same holes in the problem-solving schema that I saw in Brazil. Klein and Thompson make a compelling argument that medical schools are artificially limiting the potential supply of doctors. Their solution - remove those artificial constraints so more people can become doctors - fixes the supply problem but doesn’t address the lived experience of the problem. How can we know that more doctors in America will result in more doctors in the places that need them most? How can we be sure that more med school students will result in better care, not just more care? We can’t. They want to address the housing crisis by building more houses, but they don’t talk about how to ensure those new homes will be available for the people who need them, where they need them. It’s fine that they don’t have perfect solutions - it’s unrealistic to expect to solve complex problems in one fell swoop - but Thompson and Klein don’t seem to be acknowledging the obvious limitations to their abundance agenda.

I really admire Thompson and Klein. The abundance agenda is a rare example of a positive vision for the future that Democrats desperately need. But the holes in their problem-solving schema almost guarantee that their ideas won’t work as intended. When Coca Cola is ripping off farmers, any honest attempt at a solution requires Coca Cola to change their behavior. When we have 16 million vacant homes and nine million housing insecure people, any honest attempt at a solution requires equitably distributing our existing homes. These ideas are not mutually exclusive. Coca Cola can stabilize prices for the guaraná and the excess can be resold as a power; significant taxes on second home ownership can limit house hoarding and we can make it easier to build new housing. But until we address the core culprits in our policy solutions, things will never really change

The abundance agenda brilliantly calls for the government to clear away obstacles for delivering services. The real fight will be over identifying what obstacles need to be cleared. As this agenda is adopted by the Democrats, pay attention to how your elected officials and candidates approach problem solving. If they never discuss obvious causal factors for the problems they are trying to solve, don’t be afraid to call them out. They probably have a hole in their problem-solving schema.